Last week we celebrated World Wildlife Day.

To protect wildlife and tackle illegal and/or unsustainable trade in wildlife as a driver of biodiversity decline, TRADE Hub’s researchers analyse the volumes and characteristics of local, domestic and international trade, aiming to use their findings to protect wildlife and ensure that where trade occurs, it is ecologically sustainable.

Wildlife trade can be a driver of species loss, but where trade is sustainably managed, it also can be an important source of livelihoods in developing countries, as well as being inherent to values and traditions in communities.

Balancing conservation goals to reduce overexploitation with the needs of people can be challenging. For instance, if policies are put in place to strictly regulate the trade without adequate enforcement or demand-reduction approaches, this could lead to an unintended move towards illegal trade. Recognition of the complex socio-economic dimensions to the wildlife trade when developing wildlife trade policies is important to help ensure that the policies have the desired outcomes. A risk-based approach to wildlife trade policy development can help the development of the right policies to protect species, to ensure the trade is sustainable, and to contribute to people’s wellbeing.

In this blog, we summarise some key findings from our most recent paper on wildlife trade.

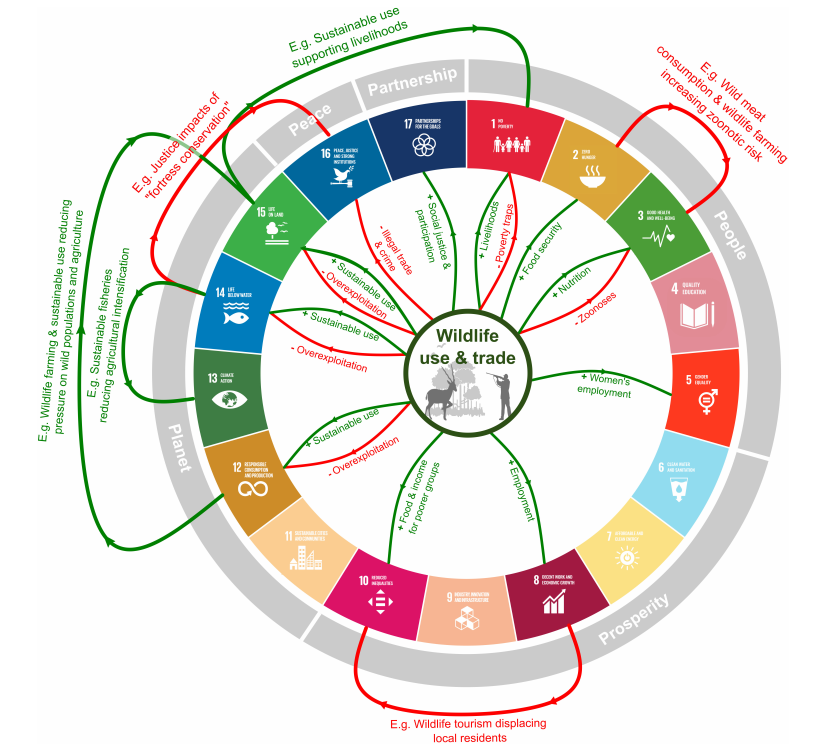

This paper, led by TRADE Hub researchers at the University of Oxford, discusses how wildlife trade policy interventions can contribute to, but may also hinder achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in some instances. Using examples, it illustrates cases in which different policy decisions, where well-designed, can help protect wildlife, promote species recovery, and make trade sustainable and socially just.

The tokay gecko, Gekko gecko, is one of the species studied by the TRADE Hub. Trade volumes of this species are high and in 2019 the tokay gecko was included in Appendix-II of CITES in order to regulate international trade levels.

The trade of wild animals is often associated with the transmission of zoonotic diseases.

The Coronavirus pandemic has brought wildlife trade into the spotlight, as it is reported to have potentially played a role in the emergence and spread of the virus, though this remains inconclusive. This has led policy-makers and governments worldwide to consider options for minimizing the zoonotic risk, which include the implementation of strict policies to regulate wildlife trade, in some cases including broad-ranging bans on trade in all wildlife or particular groups of species.

A newly published paper that TRADE Hub partners contributed to reflects on how these policies need to be carefully considered.

The authors assess post-Covid-19 wildlife trade policy options and consider how well they align with the SDGs. These policies aim to contribute positively toward the achievement of the goals, but could also have unintended consequences that hinder progress towards the SDGs. For example, the sale of bushmeat in Ghana is primarily managed by women; if this trade were to be banned or become strictly regulated without putting additional provisions in place for women, it could have unintended negative effects on gender equality (SDG 5). Therefore, such policy decisions call for careful socio-ecological analyses that take into account the effects on the “5Ps” of the SDGs: People, Prosperity, Peace, Partnerships and Planet.

A risk-based approach to wildlife trade policy is the best way forward, according to the authors.

Policy interventions should “save lives, protect livelihoods, and safeguard nature”, as stated by IPBES Expert Guest Article on Covid-19 Stimulus Measures. To do so, participatory and evidence-based approaches should be used when formulating policies, as these “explicitly acknowledge uncertainty, complexity, and conflicting values across different components of the SDGs”. Whilst strict wildlife trade bans might be necessary for species that pose a high public health risk, such as horseshoe bats, the authors note that in certain cases policies that promote a well-regulated sustainable trade of wildlife might bring more positive effects than bans.

An example is the saltwater crocodile in Australia, the sustainable trade of which facilitated the recovery of the species and now contributes ~US$ 515,000 in yearly income to Aboriginal communities through an egg harvesting initiative. This supports not only the conservation of the species, but also the achievement of zero poverty (SDG 1), zero hunger (SGD 2), and reduced inequalities (SDG 10), amongst others.

“Illustrative examples of some general positive (green) and negative (red)

contributions of wildlife trade to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Direct contributions are

denoted by arrows in the center of the diagram, while interactions between the SDGs are denoted by

arrows around the outside (with trade-offs in red and synergies in green). This diagram is illustrative

only; it is not intended to provide a complete review of all types of wildlife uses and trades, and their

contributions and interactions” (Booth et al. 2021, p. 3)

Nonetheless, such approaches require the use of data that are often lacking.

The need for large amounts of data to set wildlife trade policy and define appropriate levels of trade can slow down policy-making processes, which is not ideal during times of crisis such as a pandemic when rapid decisions must be made. This can lead to ill-informed decisions that can have detrimental effects on wildlife and the achievement of SDGs in the long term. TRADE Hub can contribute to making such processes easier through work to develop tools that contain relevant metrics and indicators related to wildlife in trade.

Work carried out by TRADE Hub partners to improve the understanding on wildlife trade has the potential to benefit wildlife and people. We look forward to the next World Wildlife Day in a year’s time, and to the progress we will have made on this important topic.

You can read the full paper on Frontiers. This includes six interesting case studies and suggests a process with key considerations for developing risk-based wildlife trade policy.

To hear more about TRADE Hub’s work, check out our research and subscribe to our newsletter.